How can we determine the success rate of a course and the number of attempts students need to pass?

This work argues that traditional pass rates based on single exam sessions (IPR) are unreliable indicators of course success, as they systematically over- or underestimate outcomes due to participation patterns, multiple attempts, and resits. To address this, the author introduces the Progressive Success Rate (PSR), which measures the proportion of students who eventually pass a course across cohorts. Using both an illustrative example and real data from several TU Delft courses, they show that PSR provides a more stable and meaningful measure of course success, complemented by the Average Number of Attempts (ANA) needed to pass.

Introduction

Currently the success rate of a course is (in practice) often assessed using the pass rates of a single exam session; we will call this the incidental pass rate (IPR). This IPR is usually computed as the quotient of all passed student and all participants in that one session. This approach has (at least) three, entirely different, systematic problems:

• Not all students of a cohort participate in an exam session, but may participate in the course.

• The students that do an exam once (and pass) are counted once in the IPR, whereas students that do an exam \(N > 1\) times before passing appear N times in the IPR. This means that the second group is (systematically) overrepresented in the IPR.

• Passed students try to use the resit to improve their grade.

The first effect means that pass rates tend to overestimate the success of a cohort, the second effect means that pass rates tend to underestimate the success of a cohort. The third effect can go both ways: some passed students do better at the resit, thus increasing the pass rate and some do worse thereby lowering the pass rate. Together, however, these three effects

make pass rates unreliable to determine the actual success rate of a course. In this work, we present an alternative measure for the success rate of a course, the progressive success rate (PSR).

Definition and computation of the PSR: an illustrative example

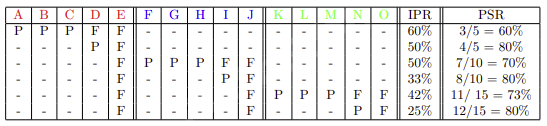

Before looking at the definition of the PSR, we consider a motivating example. We use an artificial course, that is taken every year by five students. This course has two exam opportunities every year; we follow this course for three years. The first five students are denoted by A-E, the five (new) students in the year thereafter by F-J and the final group of five is

denoted by K-O. Their exam results (Pass or Fail) are given in Table 2. We observe that the IPRs vary between 60% and 25% are steadily decreasing. These IPRs, however, do not tell the full story.

We also computed the ”Progressive Success Rate” (PSR), which is defined as follows:

\(\mathrm{PSR}=\frac{\text{Total number of passed students of all cohorts}}{\text{Total number of passed students of all cohorts present at least one exam}}\)

The PSR does not suffer from the three problems mentioned above, because

• All students are counted (if they appear at least once in the exams over the years).

• All students are counted once, independent of the number of times they participate in an exam, regardless of the number of times they need to pass the exam.

• Passed students improving their grade do lead to a higher IPR but they do not affect the PSR, because in the PSR every passed student is counted only once.

This means that the PSR is a more reliable measure for the success rate of a course. In our (artificial) example, we observe that the PSR equals 80%; four out of five students pass the exam eventually. When determining the PSR we can also compute another interesting parameter: the average number of attempts a students needs to pass the exam (ANA).

\(\mathrm{ANA}=\frac{\text{Total number of attempts of passed students until first pass}}{\text{Total number of passed students of all cohorts}}\)

In the ANA we only take passed students into account and only attempts until they pass the exam – attempts of passed students trying to improve their grade are not included. For our artificial example, this means that students E, J and O are not included in the ANA. For the other students, all attempts are included. This leads to an ANA of 15/12 = 1.25 in our example.

The PSR and ANA for three different courses at TUD

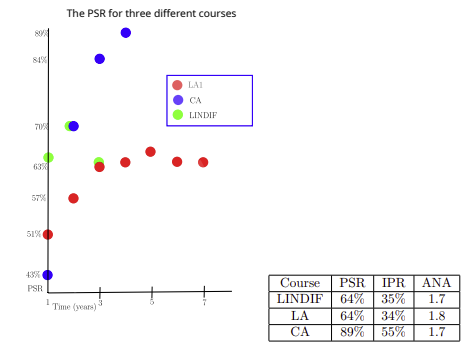

In order to determine the PSR, exam data of a course are needed in a number of consecutive years; we have analyzed data of three courses at Delft University of Technology: the results of 16 exam sessions of Linear Algebra 1 (LA1) from the Bridging program (total population: 1332 students), the results of 8 exam sessions of Complex Analysis (CA) from the Master program of Applied Physics (total population: 400 students) and the results of 6 exam sessions from Linear Algebra and Differential Equations (LINDIF) from the Bachelor program of Molecular Science and Technology (total population: 336 students). A similar analysis can be done for other courses if the data are available.

Note that we do encounter one systematic problem: what grade does a student need to pass? In general this is a 6.0, so for LA1 and LINDIF I considered a grade of 6.0 (or higher as a pass). For CA there was a compensation regulation in place, which meant that in practice a grade of 5 of higher meant a pass. In the CA-case I took the grade 5 as a pass. Furthermore, students can pass these courses in other ways: passing an exam of a similar course in another program, compensation rules that I am not aware of, etc. I can not take these effects into account, because I do not have access to the required information. This means, that, effectively the PSR will always lead to a lower bound on the percentage of passed students (students may have passed the course by different means that I am not aware of). The results are presented in Figure 1; we observe that the PSR becomes more or less constant after a couple of years.

Table 1: The PSR as function of time for LA1, CA and LINDIF (left) and the eventual PSR, IPR and ANA (right). The IPRs are determined as the (weighted) average of the IPRs of all exam sessions.

Notice that these results are similar to the results reported by Arnold [1], who found an ANA averaged over multiple courses of 1.422 (14.22 exams on average for 10 courses).

Discussion and Conclusion

We have now established a method to compute the PSR and the ANA, but how can we interpret these numbers. Let us discuss the PSR first. It is important to note that we will never reach a PSR of 100%, because

1. Some students have dropped out.

2. Some students have passed in an alternative way.

3. Some students will pass in the future.

The first effect is especially important for courses before the selection moment (like BSA) has taken place; for our courses this is the case for LA1. The PSR should not be viewed in isolation, but can be compared to similarly obtained percentages from courses in the same program/year. Specifically for first year courses we can also compare the PSR to the BSA-rate: a course with a PSR close to the BSA-rate could be the ”bottleneck” of the program. Whenever the PSR of a course is significantly lower (or higher) this could mean that there could be a problem with the course: this can, e.g., be an indication that a course is too hard (or too easy). The courses LINDIF and CA are after selection has taken place; the high PSR of CA (89%) basically means that all students have passed already/will pass the course. For LINDIF, the PSR showed a similar trend, until we saw a sudden drop in the third year. Such a drop may indicate a problem in that particular year. Indeed, this cohort had collectively adopted an ”efficient” way of studying: they used AI-generated summaries of lecture recordings

instead of attending lectures in person and they used generative AI to solve their homework exercises. This behaviour led to bad results in multiple courses. We expect this to be a one-time issue, that will resolve itself over time – we expect that the LINDIF students will adapt their study behaviour.

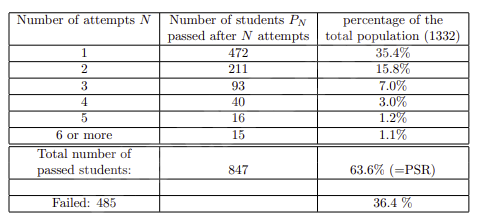

Ideally, most students pass a course in one attempt and the ANA is close to one. However, in the Netherlands this is not how part of the students approach their study. Failing an exam is not a big issue, because there is always another attempt/possibility. This is reflected in the ANA of 1.4 (reported in the literature, based on data of the Erasmus School of

Economics) and 1.7/1.8 for our courses. Note that a (very) small group of students that needs many (five or more) attempts has a relatively large impact on the ANA (see table 2). Discarding this small group of students, we find an ANA closer to 1.4/1.5, which effectively means that half of the students passes in one go and the other half needs one resit. This is

an encouraging result, because this means that these courses do not cause study delay, even though they are all considered among the most difficult of the program.

Summarizing, we conclude that the PSR should be used to assess the success of a course instead of the IPR; the PSR yields the actual percentage of passed students over the years, whereas the IPRs may yield an incorrect of the success of a course. Furthermore, another valuable parameter, the ANA can be determined in the process of determining the PSR. Both PSR and ANA of a course should preferably be considered in comparison to other PSRs and ANAs of other courses in the same program.

Appendix. Data on LA1

Table 2: Course LA1 in the bridging program, before ”selection” moment; summary of the results after 16 exam sessions.

References

[1] Ivo Arnold. Resitting or compensating a failed examination: does it affect subsequent results? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(7):1103–1117, 2017.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Bart van den Dries for his critical review of the manuscript.